The House of Mourning

A reflection on three memorial services in seven days

“It is better to go to the house of mourning than to go to the house of feasting,

for this is the end of all mankind,

and the living will lay it to heart.”

— Ecclesiastes 7:2

Last week was a heavy one. When I look back at my calendar over those seven days, I see three memorial services. Three different families. Three stories. Three gatherings — as different from each other as they could possibly be — yet all united in the presence of grief and remembrance. Three out of seven days spent in the house of mourning.

And as a bonus — if you can call it that — day four of seven wasn’t a funeral, but it was a conversation across a table with a longtime friend who disclosed that he’d received a stage-4 cancer diagnosis. This friend is certainly not gone yet, and I’m absolutely praying for a miracle. But still – an incredibly heavy meeting.

That’s not a normal week for me. Not even as a pastor. But that’s what happened. And it brought Ecclesiastes 7 to life in a way that hasn’t stopped echoing in my mind.

The End of All Mankind

Solomon says it plainly: death is “the end of all mankind.” In one sense, you might think, “That’s morbid.” To which I can only reply, “No… that’s reality.”

Most of us spend our lives trying not to think about our mortality. But funerals won’t let you look away. They force you to acknowledge what you normally suppress. In the house of mourning, we’re reminded of the truth that the party always ends — and that we don’t control when the music stops.

And in that somber light, everything suddenly looks different.

The Wisdom of Mourning

Ecclesiastes 7 is full of paradoxes:

- “Sorrow is better than laughter” (v.3)

- “The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning” (v.4)

Why? Because mourning strips us of illusion. It makes us sober. It forces us to ask: What really matters? What will remain when I’m gone?

Laughter can distract, but mourning awakens. It wakes us up to the brevity of life — and the urgency of living it well.

We spend so much of our lives worrying about and chasing things that, on our final day, really won’t matter. I deeply resonated when I saw Rick Warren, author of The Purpose Driven Life, recently exhorting a group of graduates:

“I have sat by the bedside of maybe thousands of people as they took their last breath… and nobody has ever said to me, ‘Pastor Rick, bring me my trophies, I want to look at them one more time.’ Or even, ‘Bring me my college diploma — I just want to hold it one last time.’”

My experience is only in the dozens, not the thousands. But I’ve definitely observed the same.

Never once have I talked to someone on hospice, or with a stage-4 diagnosis, or on a deathbed, and heard them say:

- “Gosh, I wish I had gained more TikTok followers...”

- “I should’ve remodeled the kitchen one last time…”

- “I wish I had worked more Saturdays…”

- “I regret not upgrading to the SUV…”

- "If only I could have spent more time arguing on Facebook."

The house of mourning has a way of stripping away our illusions and helping us see what actually matters.

Three Stories

Last week, I participated in a service for a man whose quiet faithfulness spoke louder than a thousand sermons. A long life, well lived. I was honored to joyously pound out some classic old hymns on the piano at this very large gathering. Though he’s certainly missed and there were still plenty of tears, it was a blessing to celebrate his life.

I also officiated a service remembering a young life gone far too soon — grief rippling through coworkers, relatives, and stunned friends who hadn’t yet imagined that death could come this close. Armed with only the Gospel, I tried to offer hope to a room where I’m certain the vast majority did not share the faith of the deceased.

And then I stood for a couple hours at a humble outdoor gathering remembering my own uncle. His old bandmates played live music without him. His sons — my cousins, whom I hadn’t seen in over a quarter-century — were still trying to process losing their dad. Hours of bittersweet conversation led to one piercing question: Why does something like this have to happen to bring us together again?

Different lives. Different legacies. But the same reality: this life doesn’t last.

The Living Will Lay It to Heart

When I read that verse from Ecclesiastes, this is the phrase that lingers: “The living will lay it to heart.”

Solomon isn’t glorifying sorrow for its own sake. The house of mourning is not better because grief is enjoyable. He’s saying something deeper: death has a lesson for the living. And the wise will listen.

Some will leave a funeral and go back to pretending they’re immortal. Others will walk away sobered — and changed. They will lay it to heart.

They’ll forgive, and let go of that grudge.

They’ll spend more time with their children.

They’ll pray again.

They’ll call their parents.

They’ll say “I love you.”

They’ll ask themselves — maybe for the first time — what comes after this?

Mourning with Hope

As a Christian, I don’t believe the house of mourning has the final word. But I do believe it tells the truth — a truth the house of feasting often labors to avoid.

And I believe that in the shadow of death, we meet a Savior who has tasted it — and overcome it.

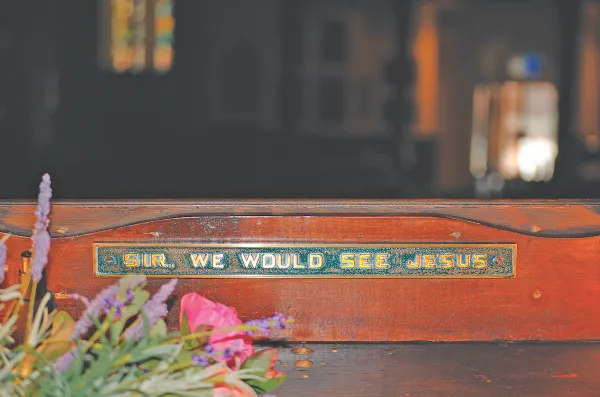

Jesus went to the house of mourning too. He stood outside a tomb and wept (John 11). Then he called Lazarus forth.

And he himself entered death so he could defeat it.

So now, even in the house of mourning, we can sing. Not because we don’t grieve, but because we don’t grieve without hope (1 Thess. 4:13). Christ has gone ahead of us. And he has risen.

Lay It to Heart

So the next time you go to a funeral — or especially if you’ve been to one lately — let it speak.

Don’t rush past the ache.

Don’t numb yourself with noise.

Ask the hard questions.

And let the Spirit of God stir a deeper wisdom in your soul.

The house of mourning is hard to enter. But it may be the place your heart finally wakes up.